Reading time: About 6 minutes

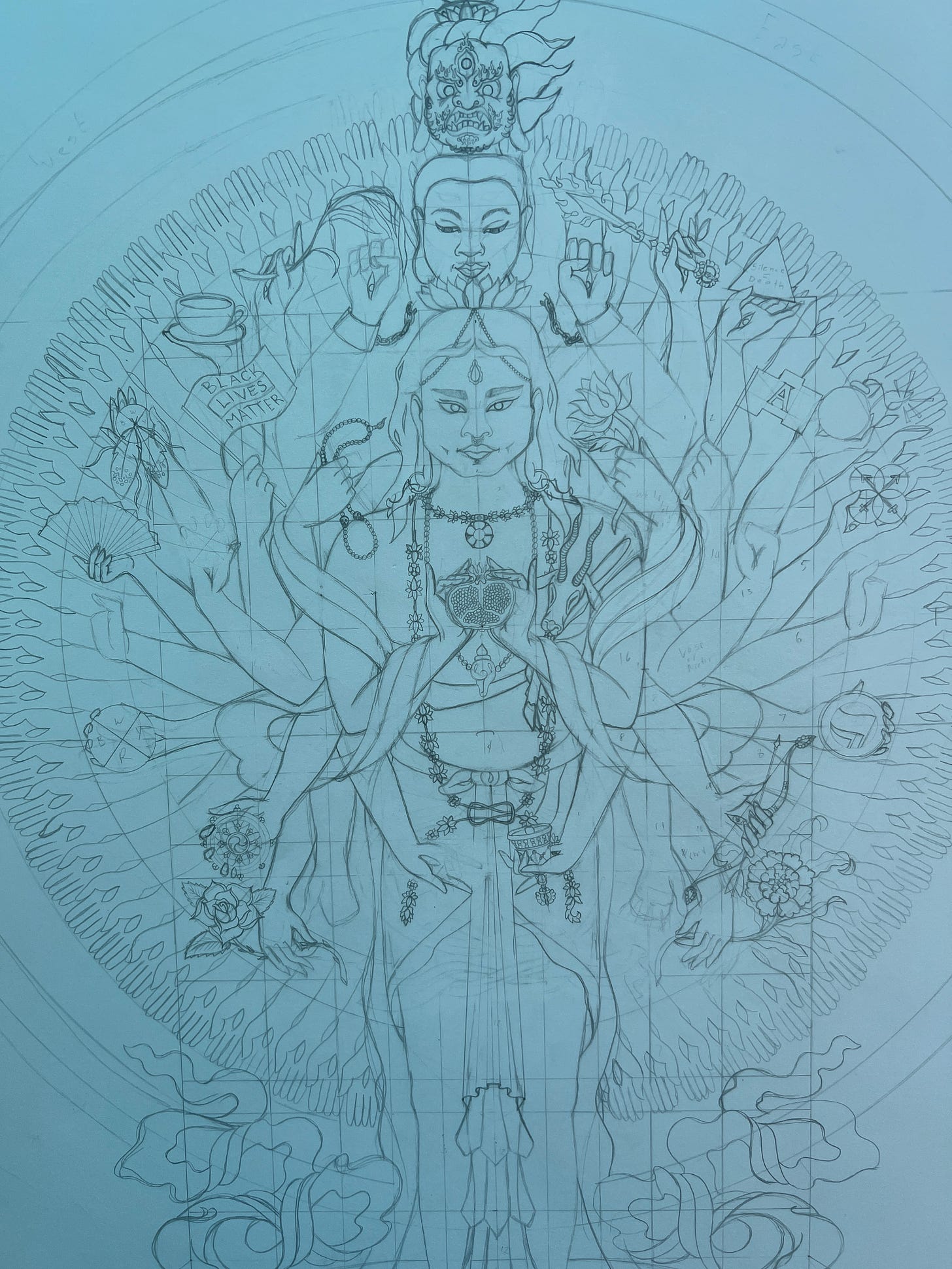

One of the first stories I heard about Avalokiteshvara was about how they came to have a thousand arms and hands. The story goes that Avalokiteshvara wanted so badly to serve all beings—to respond to the suffering of the world—they either exploded or liquefied, depending on the source and translation. They were so overwhelmed with their longing and commitment, it was just too much for their body to contain.

Buddha Amitabha1 saw this and again, depending on the telling, built them a new body with a thousand arms and a thousand hands and on every hand an eye. In another telling, Amitabha called upon Vajrapani2 to assist, the former giving Avalokiteshvara a Buddha body capable of serving and the latter cutting their new form open with a diamond lightning bolt, releasing the arms from within. The result is a being who can and does respond to all suffering.

With this story in mind, one of the first questions that arose when I began this practice with Chenrezig3 was: When are all the hands?

As an activist I reflect on the lineages of liberation I belong to. I consider the ancestors I’m related to not by blood but by a commitment to getting free. I think of the moment of Avalokiteshvara’s new form coming to be and how any one of us at any time may be an aspect of that form. A thousand hands to serve, each one representative of a time and place and movement, and within each movement, thousands of beings committed to liberation.

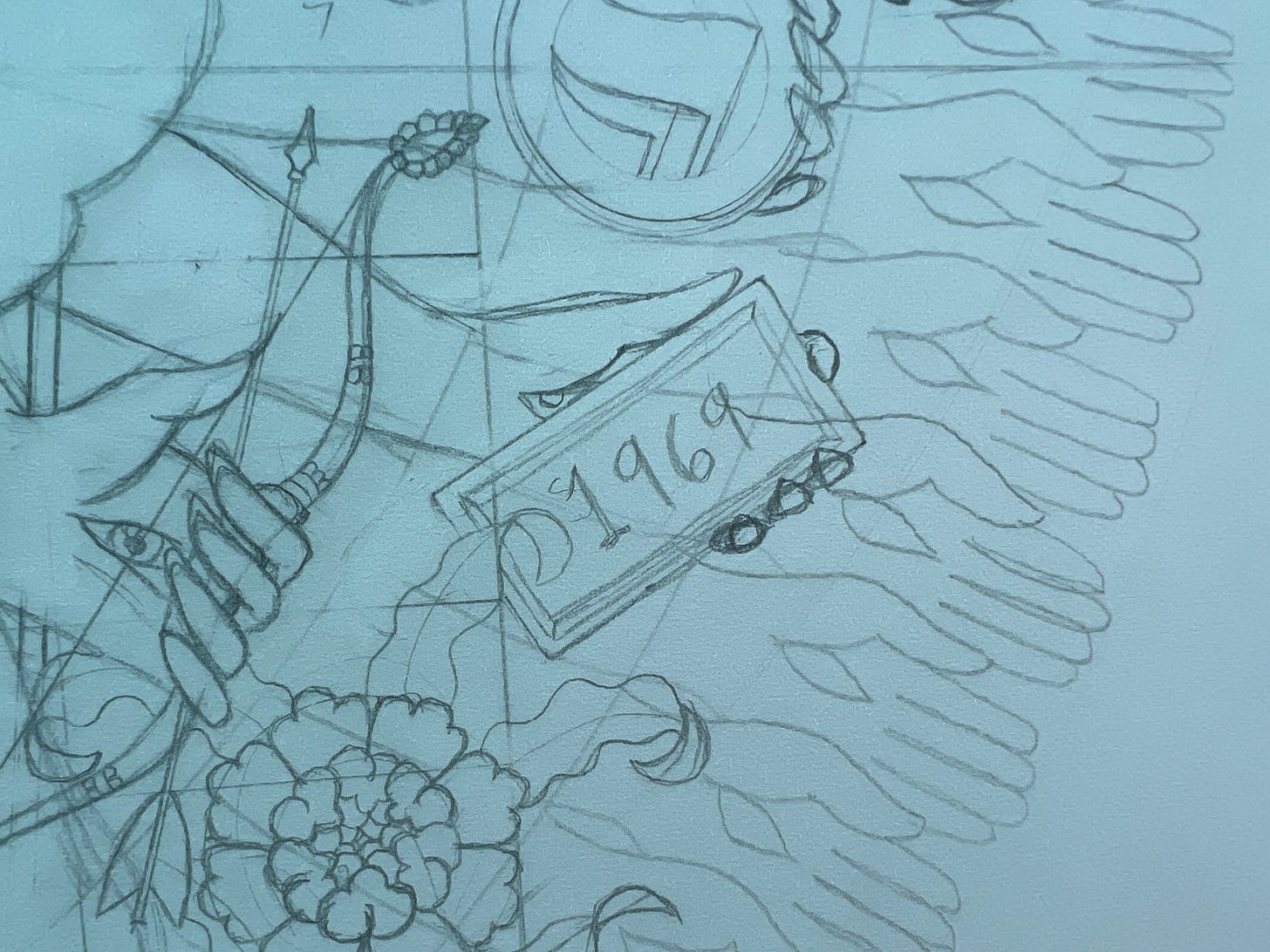

Because the figure of Guanyin4 represents compassionate action, the hands can be found in all our lineages of liberation. For me, one of the strongest lineages is that of queer liberation. Every 2SILGBTQ+ person who ever questioned, resisted, and dismantled any aspect of systemic oppression could be recognised as a hand: Avalokiteshvara is Sylvia Rivera fighting to get on stage at a Pride event so she can call out the complacency of white middle-class gay folks who think the fight is won. Avalokiteshvara is every queer person who picked up a rock at Stonewall and fought back against the cops who were “just doing their jobs” because queerness was illegal and cops are notorious for upholding unjust laws. Avalokiteshvara is Stormé DeLarverie reflecting on Stonewall and calling it a revolution, an uprising, not a damn riot. Avalokiteshvara is Bayard Rustin making connections between Black liberation, queer liberation, and worker’s rights and how any path to liberation benefits all of us. Avalokiteshvara is drag queens and kings and transgender folks refusing to let the system pathologise our existence. Avalokiteshvara is Leslie Feinberg advocating for class solidarity and solidarity within and without queer movement spaces. Avalokiteshvara is Lou Sullivan creating resources for transmasc folks because he didn’t want others to struggle alone like he had to for so long. Avalokiteshvara is every member of ACT UP showing up again and again, demanding equity in health care. Avalokiteshvara is reclaiming words weaponised against us and shouting them with pride, refusing to be bowed by shame and the narrow, false beliefs that sex and gender and sexuality are binaries.

When I look at Avalokiteshvara, I see my queer ancestors fighting to live their lives in a society that criminalised their very existence. I recognize that this fight has not ended despite the wins of queer imagination, as bigots try to present their bigotry as “simply a different point of view” while hiding behind free-speech and semantics just as they have always done through history. The way that nominalization strips nouns from language with the aim of erasing people: “I’m not against trans people, I’m against transgenderism.”5

Liberation is a grand project of imagining different possibilities for how to be in relationship. While we are all living in the imagination of greedy land owning profiteering white cisgender and heterosexual people, we are also living in the imagination of ancestors who wanted to break free from oppression.

When my partner was having a medical crisis, no one could bar me from being with her, from spending the night in a hospital room next to the person I choose to build a life with. This wouldn’t have been guaranteed to me prior to 2005 in Canada. It certainly wasn’t a reality for any queer people in 1985, the year I was born.

At the time of this health crisis, we were in the States, which had only recognised “same-sex” marriage ten years after Canada in 2015. At the time, we had only been legally certain of being counted as “family” according to society for three years.

Consider this: There are people only a generation older than me who were kept apart from the most significant person in their lives by medical staff during medical emergencies because it was perfectly legal for them to do so. Because the legitimacy of a queer relationship was not protected, any homophobe who wanted to was capable of preventing someone from knowing the floor or room where their partner was, never mind the very status of their condition.

Consider also: This right is so freshly won that bigots continue to fight against it, to try to roll it back on the basis of their personal religious beliefs and who they think gets to count as a human being.

The hands stretch back through time, reaching up and bending the arc of history towards justice. When I look at this image and consider all my ancestors, I think of the generations younger than me and those yet born, and hope my own hands might be counted amongst the thousands.

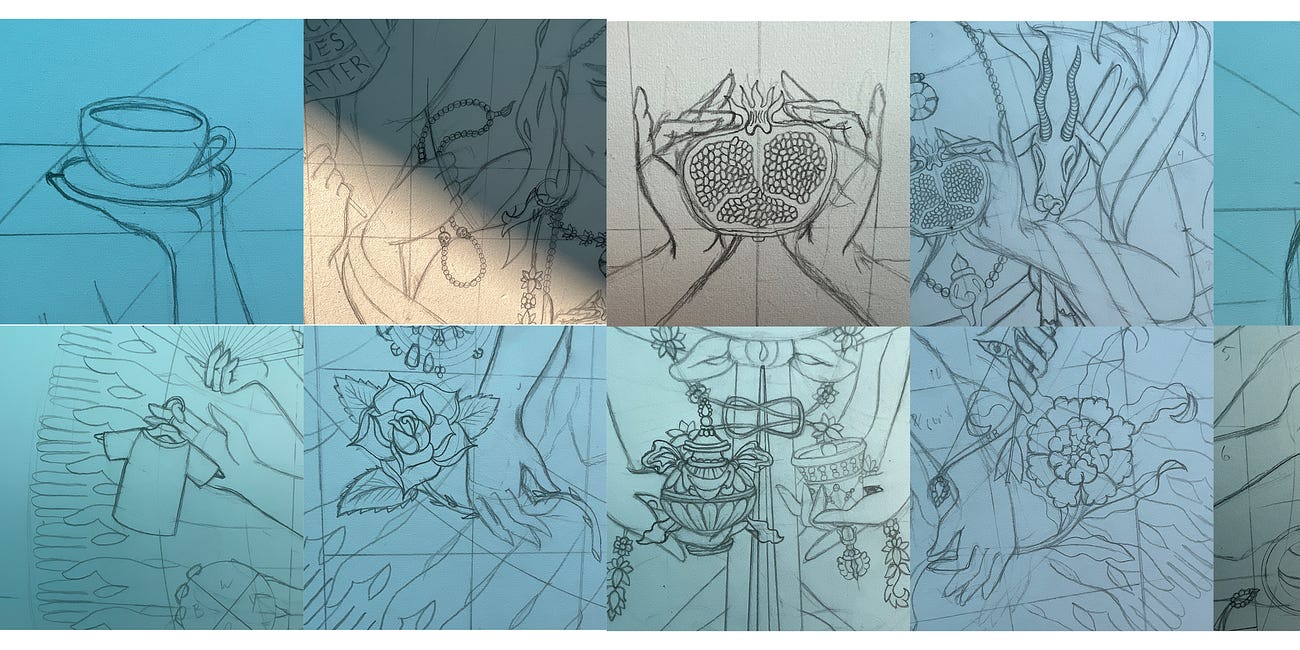

This piece is now complete and there is an online guide to all the ancestors and all the symbols that appear on it.

Amitabha is one of the five Buddhas of the Five Families I recreated for Representation Matters. Their realm is one of compassion and for many Buddhists, is the Buddha realm it is thought to be most beneficial to be reborn into.

Vajrapani is one of many wrathful deities found in Buddhist sutras and imagery. I have long appreciated the way Buddhism shows sacred forms of anger.

A reminder that Avalokiteshvara has many names. Chenrezig is their Tibetan moniker.

This is the most common name for Avalokiteshvara in China, although they have a few different names there.

See as well “ I’m not against Black people, I’m against Black Power.” Or “It’s not that I am against Jewish people, I’m just against the Jewry.” The thing about oppressive systems is that the script is the same. Erase the humans from the script and maybe people won’t notice that the aim is to erase a particular group of humans from society.