It was a sports massage therapist who told me there was a name for the particulars of my body. I was twenty-five, used to seeing massage therapists who treated the knots in my shoulders as a challenge, and were baffled by the way I was tickled by pressure that should have been painful. None of the half a dozen I’d seen before, nor the two physio-therapists, nor three different family doctors, had ever recognized that there could be a diagnosis found in the sinew of my muscles and tendons.

I can’t remember the sports massage therapist’s name, but I remember her face and her enthusiasm. She was young, close to my age, and she would come to love working on my clenched muscles and knots of such significance we named them together.

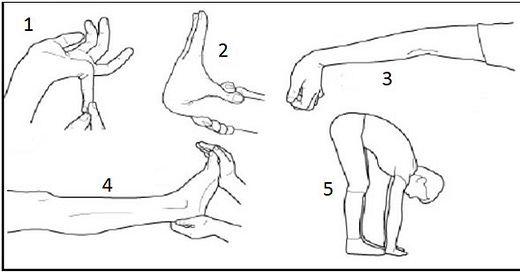

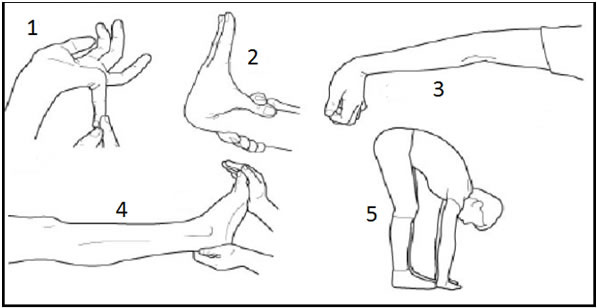

Our very first session though—before she got to know the specifics of the ropey knot down the left side of my spine (Bruce) or the tension in my calves or the pull of muscle that often pinched the vertebrae in my neck—she listened to me explain about what hurt and where. She listened and nodded, thoughtfully, and then she asked me to perform a series of motions. She had me stand and hold my arms out straight, palms up, looking at the alignment of my elbows. She watched me demonstrate my noodle neck, the way I can touch my ear to my shoulder with no effort. She had me bend back pinkies and thumbs and stand with my knees locked so she could see the curve of my legs.

“You’re hypermobile,” she said.

This moment was not too dissimilar to when my doctor, several years prior, told me I might be celiac and should cut out gluten. I was curious to encounter a diagnosis and a word I’d never heard before.

“Hypermobile? What’s that?” I asked just as I’d asked, “Celiac? Okay. What’s gluten?”1

“Double-jointed. Or, that’s what people generally call it, but it’s more complicated than that,” she said, in explanation.

It is more complicated than that, as I learned after our session, when I went home to search this new-to-me term. Many of the articles I found started with asking if you were the sort of child who would contort your body for the entertainment of your friends. I recalled my incredible back arches, unrivalled by my peers. Or how I liked to put both feet behind my head, turning myself into a sort of pretzel human. And of course, my party trick of extending my jaw so much I could fit my teeth around the bottom of a pop can.

Scrolling through pages of research, diagnostics, and anecdotes, I discovered a reason for my sensitivity to needles, my tender muscles, vasovagal dizziness and, oh yes, developing celiac later in life.2

It is powerful and strange to be able to name the particulars of your experience when you did not know that your experience was particular.

My hypermobile body had often been the centre of attention but never had it been given a name before. Prior to the gift of diagnosis, I was unaware that extending as far as my elongated tendons would allow was not good for me. I didn’t understand that not everyone woke up with a headache, or expected to develop one, nearly every day. I had no way of knowing that almost every odd and unusual health development in my life was linked by a single condition.

People with Hypermobility spectrum disorder3, have fondly adopted ‘Zebra’ as our community name. We all have stripes, but our patterns are unique. Some of us bruise easily, while others have stretchy skin. Some have found support from mobility devices since an early age while others have found the blessing of a cane or scooter or chair later in life. Some of us continue to be able to put our hands flat against the floor while keeping our legs straight, while others find our muscles too tight after all our childhood contortions.

The Medical Model of medicine doesn’t do well with ambiguity and variance. This is probably why so many of us spend years undiagnosed. It’s also probably a contributing factor to the doubt we zebras get even with a diagnosis. I have been dismissed, scoffed at, and outright mocked by medical professionals. Perhaps because they disbelieve that hypermobility exists (“You’re just flexible”) or think I’ve just picked something to make myself sound “special” (“Actually, what you’re describing is very common. Most people experience XYZ.”) That, or the legitimacy of my diagnosis is considered unreliable (“Did your naturopath or something tell you that?”)

It can be infuriating to know there is a name for the particulars of your experience and be told your experience isn’t real.

Still…

There was that first sports massage therapist, who listened to all the things I’d told so many people before and gave me a name for something about myself that had always been there.

There was the general practitioner, years later, who didn’t hesitate to support me in my quest for what counts as a “formal diagnosis” by referring me to a specialist.4

And there was the specialist, a rheumatologist, who ran me through the exact same tests as that sports massage therapist, a full decade later, and said, “Well, you’re hypermobile! But of course. I’m not telling you anything you didn’t already know.”

To be believed is validating.

To be validated is liberating.

This is the gift of a diagnosis.

I like to say I became celiac before it was cool. Back in the day of my diagnosis, no one had heard of celiac and I was asked to explain it regularly. The one perk I can say for the “fad diet” aspect of people not allergic to gluten cutting it out, has been the vast improvement of alternatives since those early days—when a loaf of gluten free bread was not much larger than Melba toast, and somehow, even drier.

Often, even when I tell people I could eat whatever I wanted as a kid and had zero allergies, there is the assumption that I was *secretly* always allergic to gluten, but it didn’t become a problem until I was nineteen. It never ceases to amaze me the audacity of some people when it comes to telling someone that they know your body better than you do.

Or Ehlers-Danlos, Marfans, or any number of similar, related, off-shoot connective-tissue conditions. You can learn a lot about the bendy spoonie community through the Ehlers-Danlos society.

Fun fact! A diagnosis of hypermobility from a sport massage therapist apparently cannot be considered official! And of course, there is no way I could be the expert on my own experience, so this lack of official diagnosis contributed to a lot of the previously mentioned disbelief and mockery from medical professionals, although even with a diagnosis, I’ve had to deal with dismissive treatment and disbelief.