Reading time: About 8 minutes

Since completing this piece I have also made a full online guide to every ancestor and symbol. You can visit the website for this by clicking the button below.

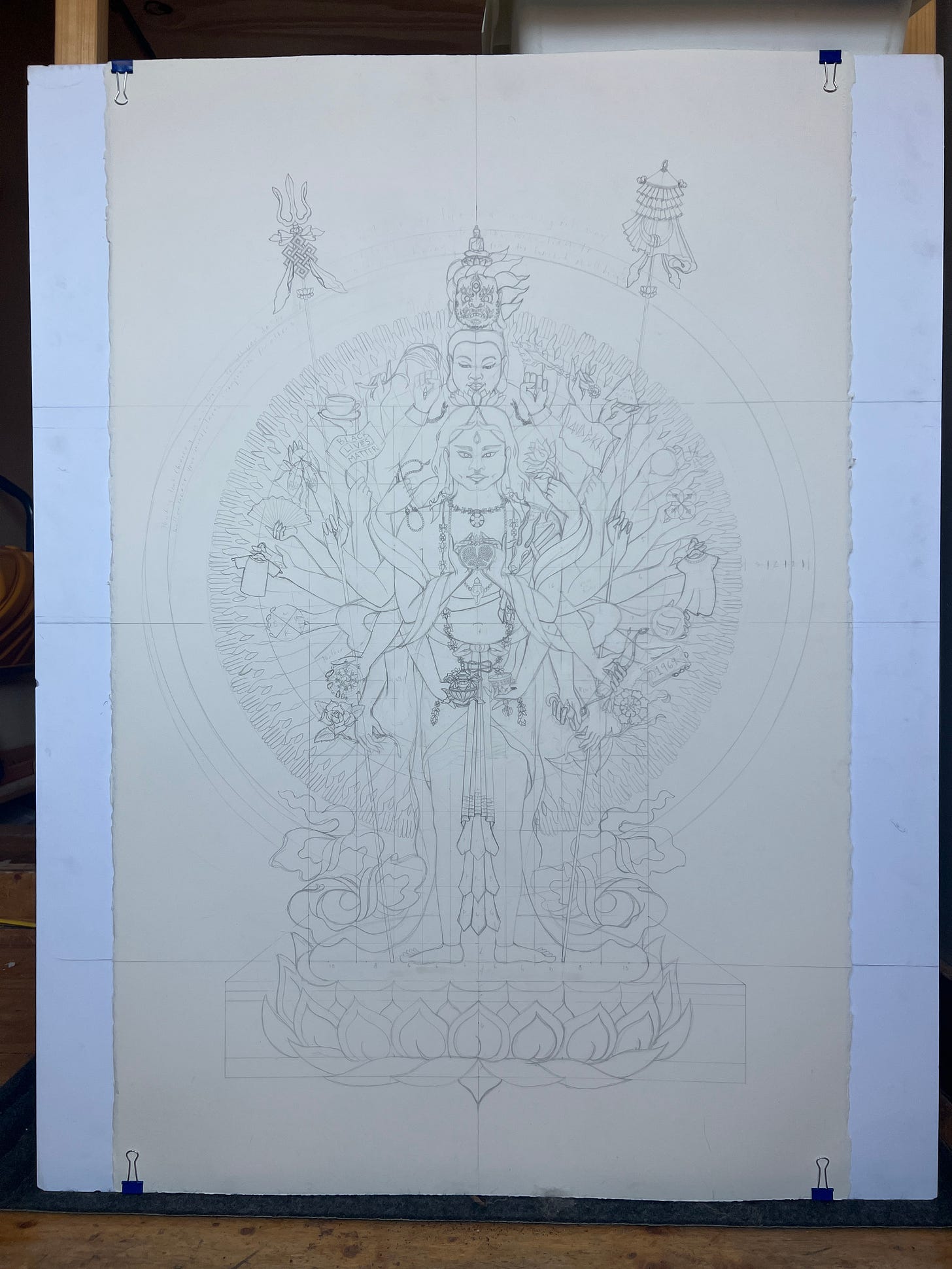

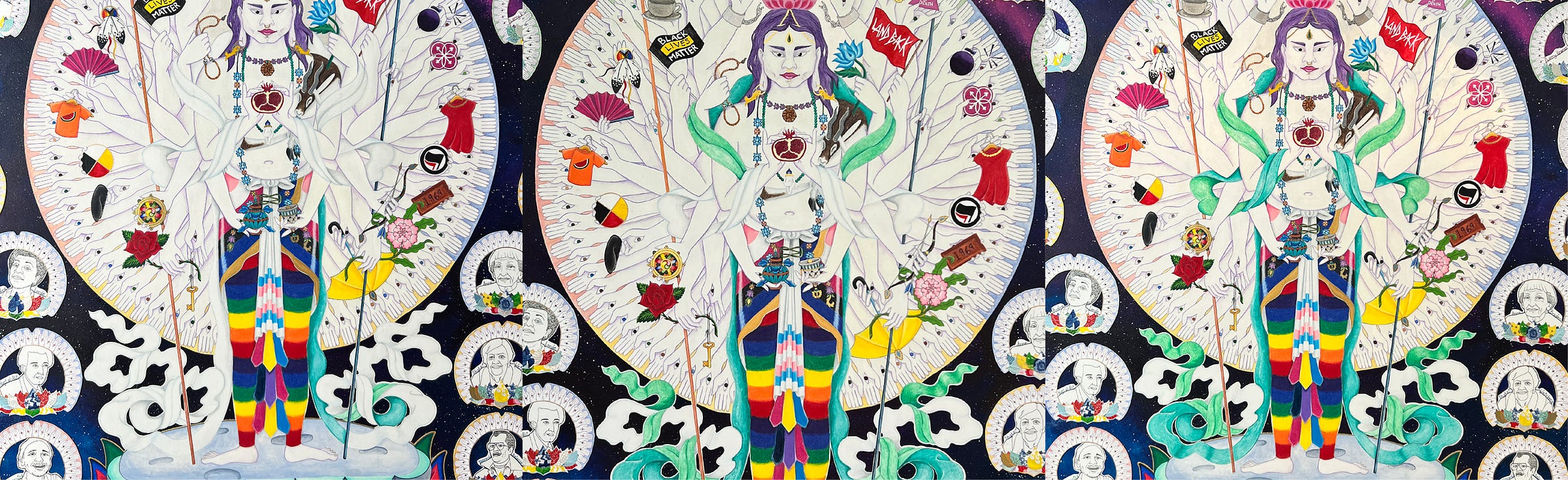

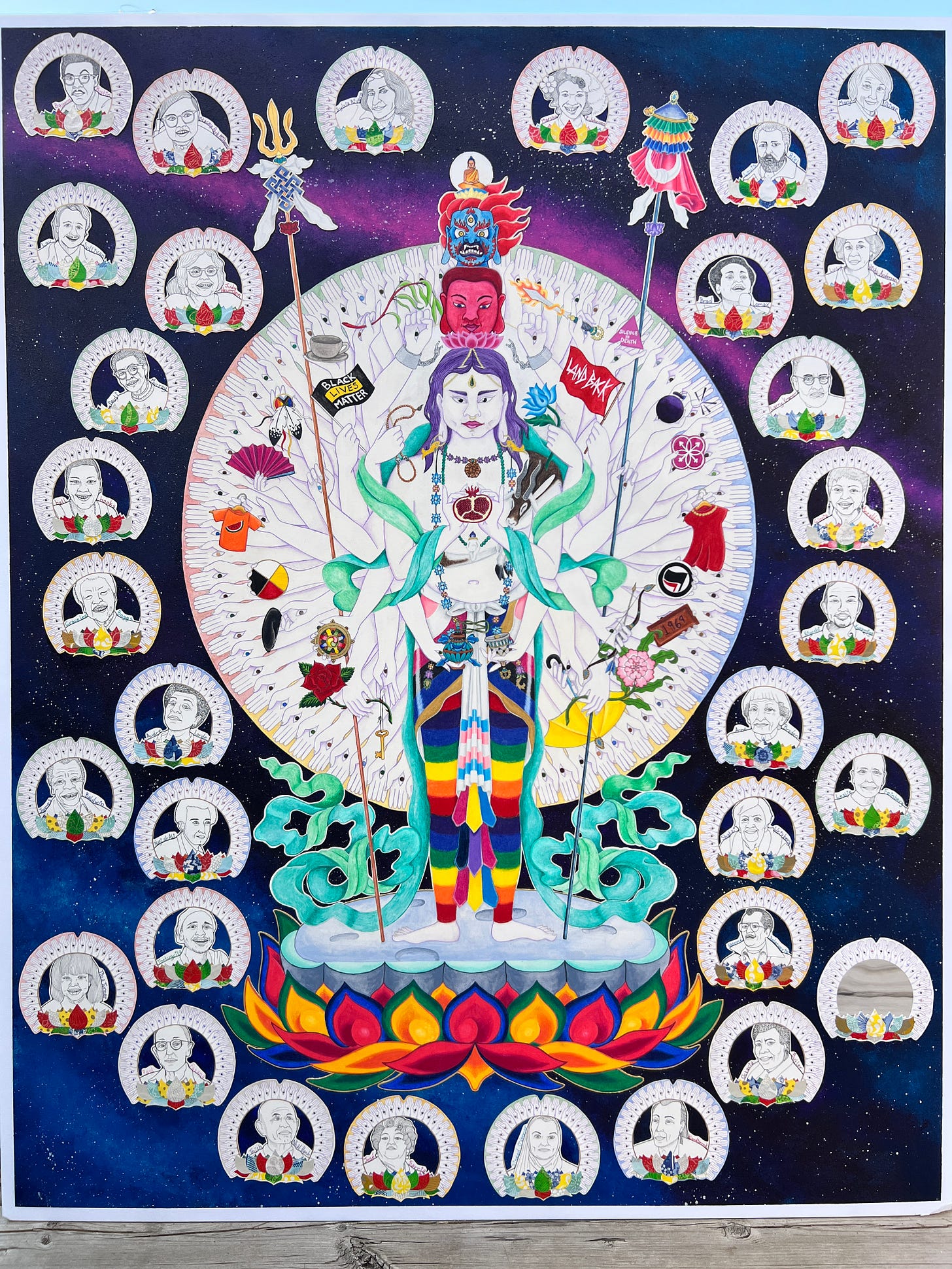

When I set out to create a contemporary image of the Thousand-Armed Avalokiteshvara, I knew it would be a significant project. I estimated it would take a year, while my patron, kindly, graciously, gave me two.

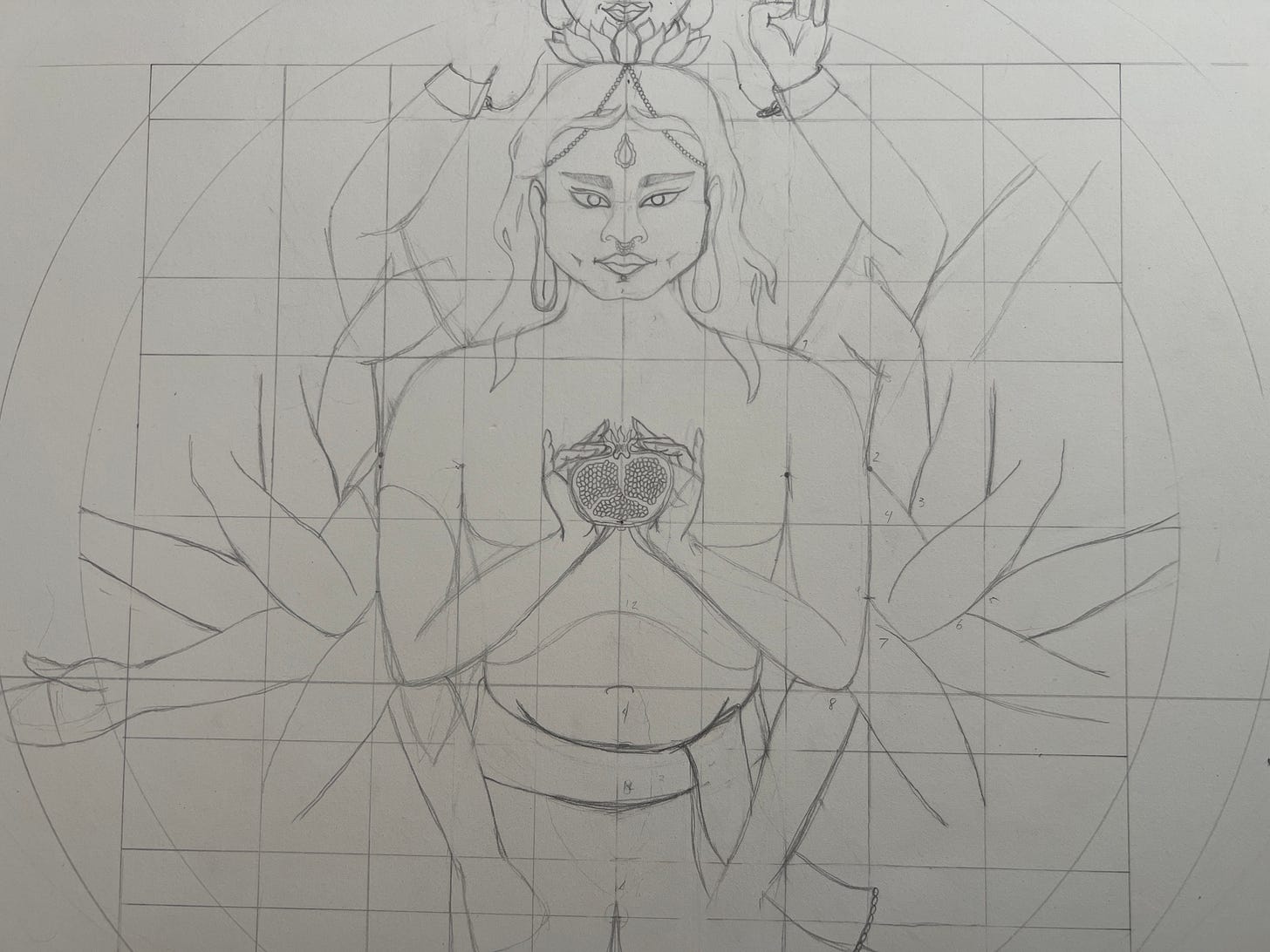

In the beginning there were technical fits and starts. None of my reference materials showed the correct grid for this complex, multi-faceted Bodhisattva. But I didn’t worry. I worked on trying to figure it out on my own, and then a friend sent me some reference books for thangka art and in the appendices of one, I found the grid.

After the grid was drawn and I sketched the figure, I came once again to a block. I figured out the math for the hands and counted them correctly, but drew the wrong number in the inner ring. I didn’t notice my mistake until the day after. I sat with it. Let it be what it was. Didn’t stress. Didn’t worry.

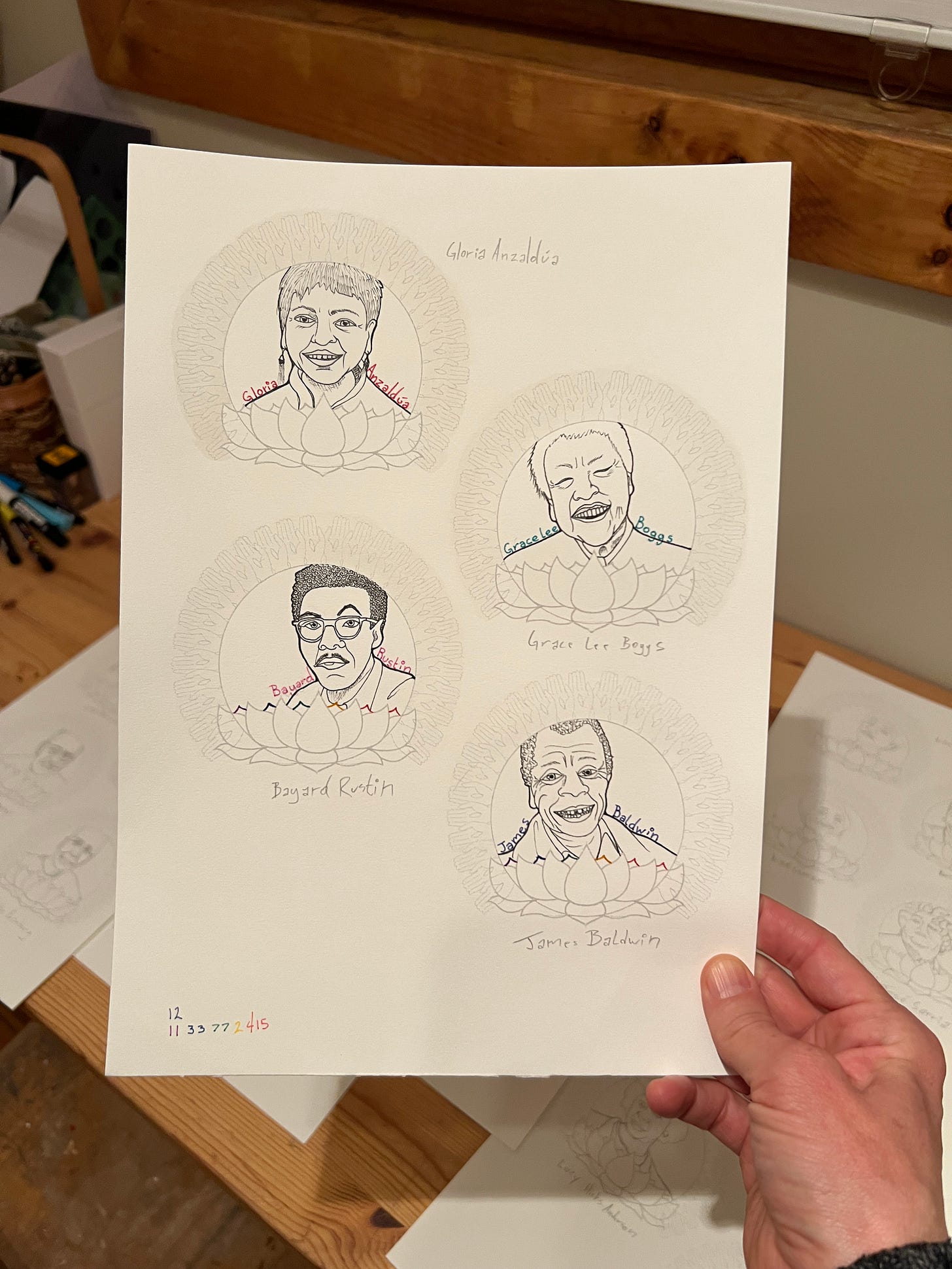

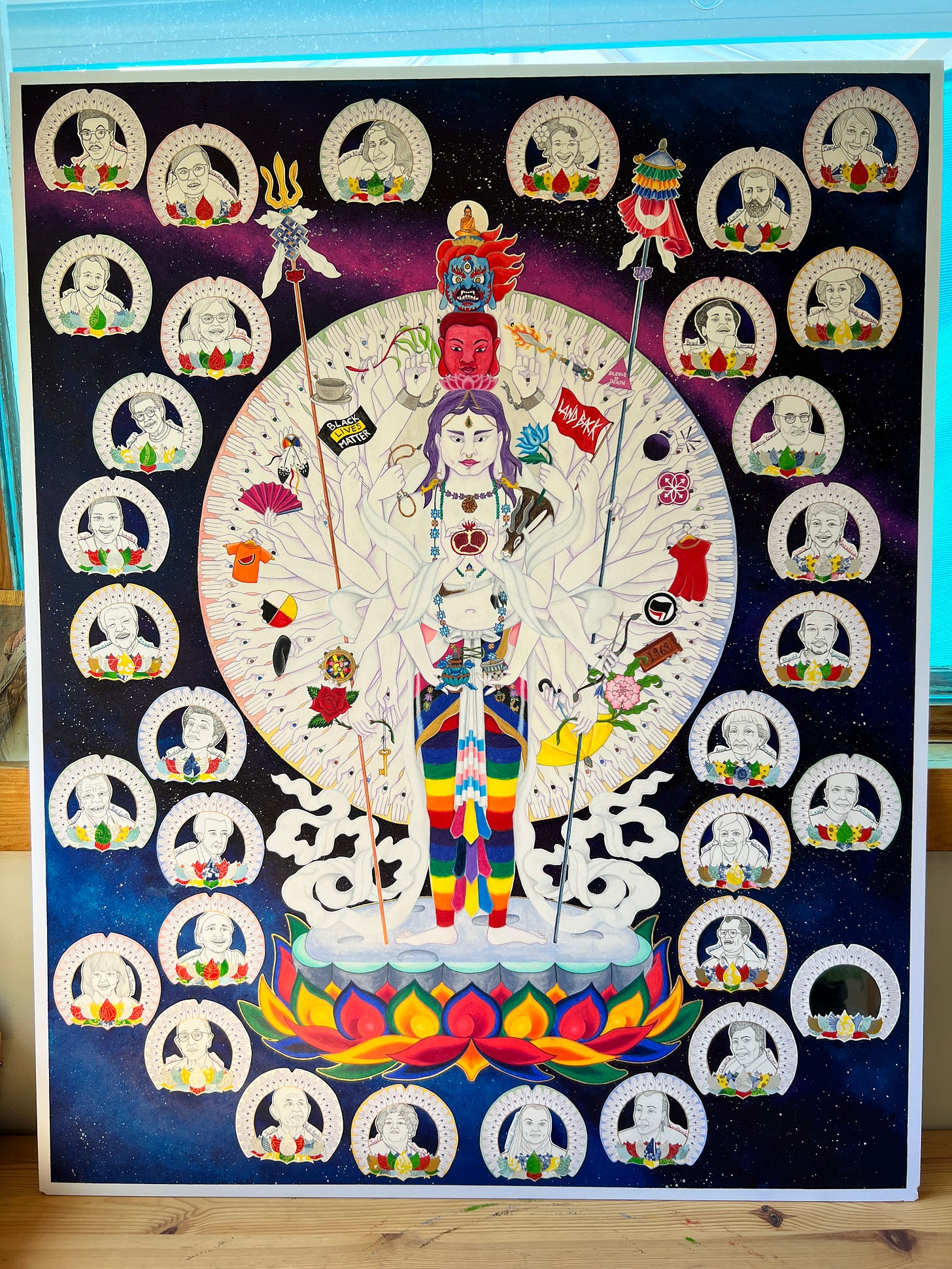

A week passed and then I had a dream of ancestors surrounding the main figure, each with their own array of hands.

I continued the work with ease, the figure showing themself in parts. Every day, after my morning routine, I would sit before the image and let them tell me what was next to draw.

I researched other pieces, I researched symbols, I researched ancestors. I made notes on the meaning of colours. I read the books my friend sent me. I drew and I drew and then…

the figure was ready for colour.

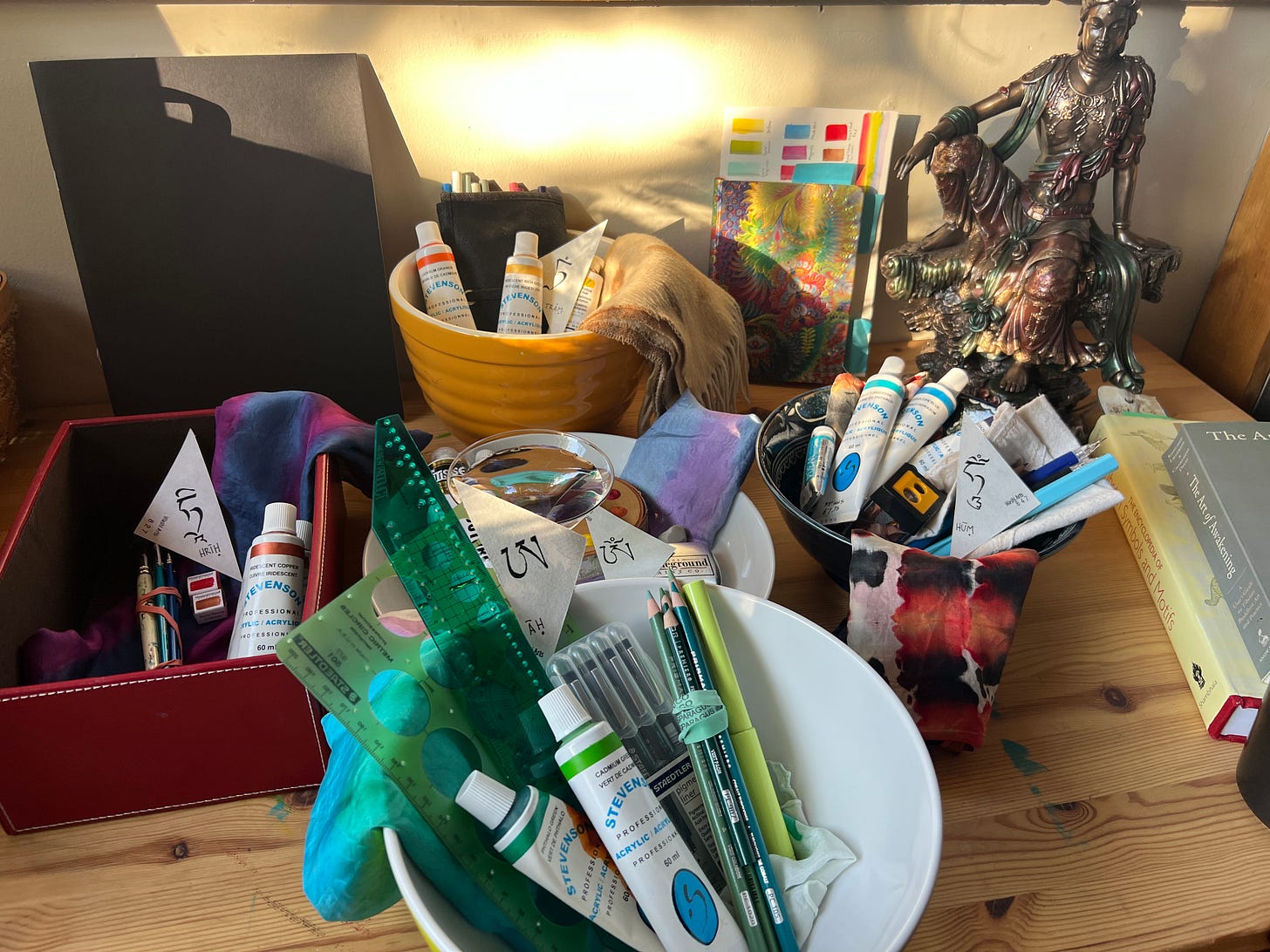

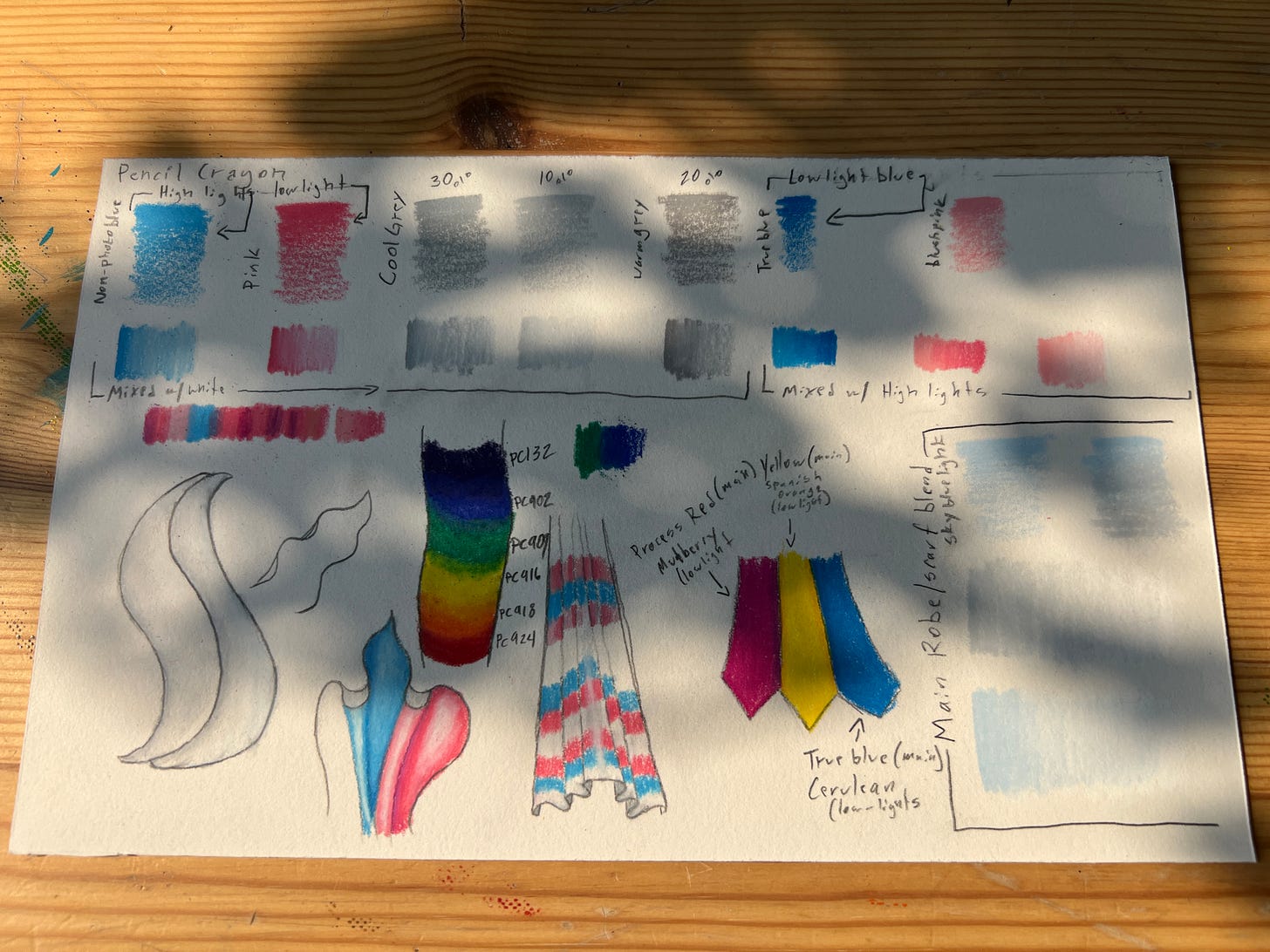

I took my time selecting materials and, following the guidance in The Art of Awakening by Konchog Lhadrepa & Charlotte Davis, held a blessing ceremony. I prepared a chant to open each session with the piece. I cleaned and prepared the areas where I would work on it and on August 16th, 2023 I began to add colour.

For the first four years of my Thangka practice, I did not add colour to the pieces I made. They remained line art. Something about colour was too intimidating. Even when I began to create colourful version of the five Buddhas, I would feel apprehensive, but as I started adding colour to this piece, I felt calm. Whatever would be would be.

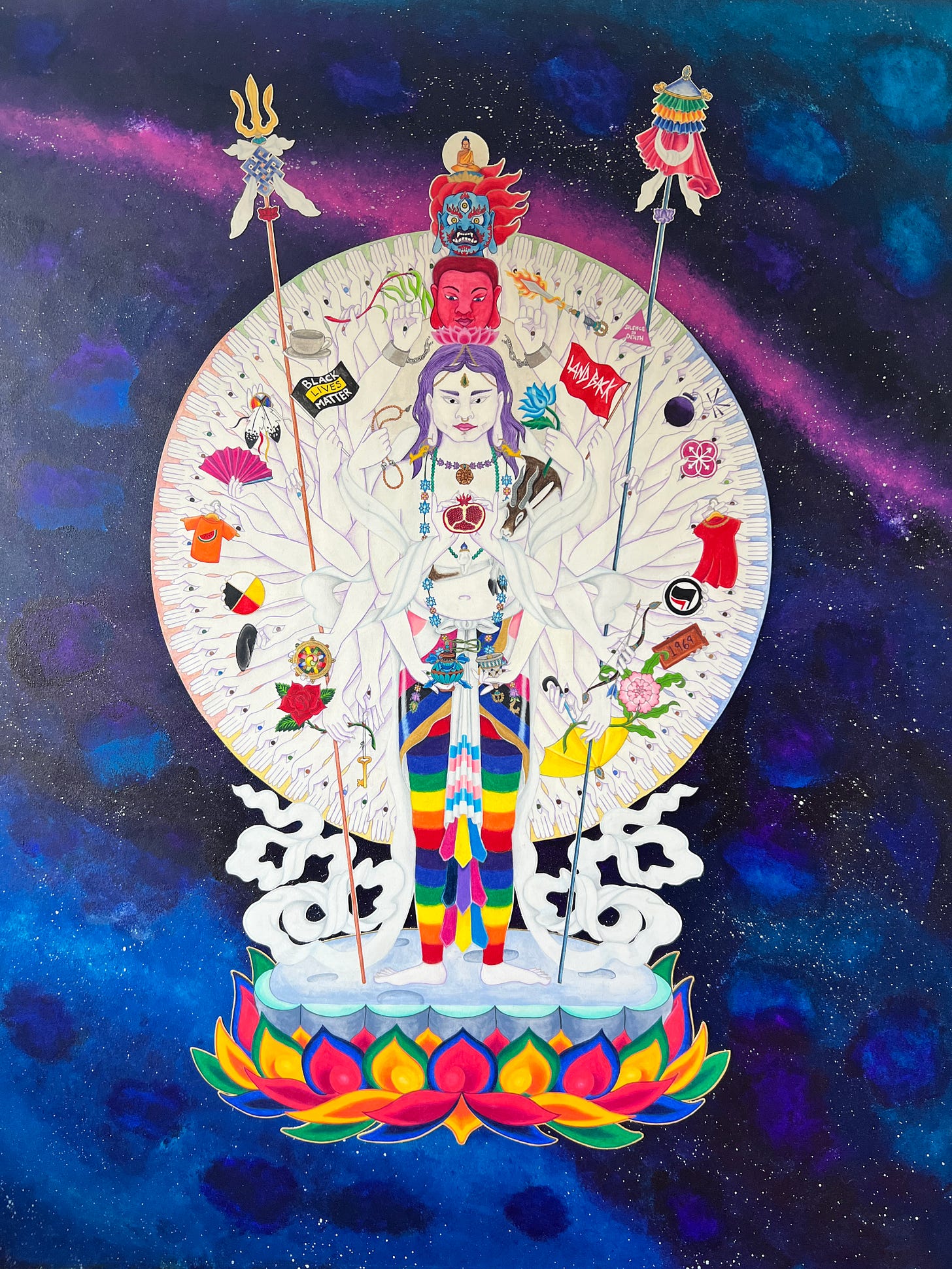

I felt so certain of the colours too. I knew the scarf wrapped around the main figure would be white. It was one of the first things I coloured in, using pencil crayon.1 I knew the left side staff would be blue, for Vajrayana, and the right a reddish hue for Amitabha. I knew they would wear rainbow leggings and I would incorporate other Pride flags into their clothing in different ways.

I was not bothered that I wasn’t sure about what colour the main figure or the background would be. I was not bothered that I hadn’t yet figured out exactly which thirty-two ancestors I could choose to surround the main figure. I was never worried or overwhelmed by the project. I rarely thought ahead to the completed piece. Each session I was present with what was, knowing vaguely the different aspects that needed to be done, but only ever focusing on one thing at a time.

Each aspect came to me differently. Sometimes in dreams, sometimes during meditation, sometimes whilst out on a walk or listening to a particular song. I regularly looked at other depictions of this powerful being, letting the lineage of artists inform me.

Avalokiteshvara exists in all realms, but their body is made of the white light of Vairocana’s realm. I dreamed the figure as made of bright light, tinged purple and towards the end of 2023 I began painting them thusly.

Something in my heart and mind tipped into an alarm state in late January. For four months we had been watching a genocide in real time. Even without watching the news, I knew the reality of what was happening in the world, and my heart was breaking for it. Breaking for the helplessness and the fatigue of so much grief. It felt like there are thousands of us calling for an end to the violence and like our cries are landing no where, moving no one who actually has the power to do anything to stop it. I wanted to be a thousand-armed being, big enough to hold it all: The grief, the rage, the devastation, the heartbreak, the helplessness.

The cries of the world overwhelmed me.

I felt broken apart at the thought of the death of entire families and multiple generations. I was full of rage at the indifference of some of the most powerful governments in the world, and the lie that there was justification to the Israeli government murdering civilians.

More than ever, the need to invoke Avalokiteshvara’s deep, abiding compassion and Amitabha’s beloved community and Vajrapani’s wrathful protection, called to me.

I sought guidance from a Dharma teacher, who instructed me to figure out a way to call in the ancestors. I knew then that the time had come to go through the list I’d made of people whose life’s work was on the path of liberation and justice.

It is challenging to make detailed artwork when your body is flooded with cortisol. Still, I was pulled to spend time with the ancestors. I wasn’t sleeping for much of February and I would find myself at my art desk in the darkest hours before the dawn. I looked at each of their faces and knowing they too had lived through hard and painful times: Previous rises of fascism, the AIDS epidemic and indifferent governments, criminalization of queerness, occupied homelands, they or their ancestors enslaved, disenfranchised, made to be refugees.

I drew the last of the ancestor portraits on March 4th, 2024.

By late spring 2024, I knew the background would be a glorious galaxy full of stars. I was nearing the end of the project, the timeline no longer the unanswerable question of the length of a piece of string. I could feel that the piece would be done very soon.

On June 28th, 2024 I glued down the final ancestors: Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson. Fitting, as this was the anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall Revolt, which may or may not have started when another ancestor on this piece, Stormé DeLarverie, punched a cop attempting to cuff her.

The next day I painted Hrih, the seed syllable of Avalokiteshvara, on the back.2 Technically, I was done. Every step from drawing the grid to sketching the figure to adding colour to conceiving of a background, was complete. The only thing remaining was to spray seal it to protect it.

And yet…

Something felt incomplete. I kept putting off sealing it, for a day and then three. On the fourth day my patron texted me. He was hesitant but wanted to ask if maybe, possibly, I was open to creating more contrast within the main figure by changing the colour of the scarf. He was very clear it was entirely up to me, and he respected my vision, but he thought possibly a darker colour on the scarf would tie the image together more with the darkness of the background.

He was not the first to ask this.

My wife, when I told her I was nearly done, asked if the scarf was going to stay white. And another friend said it looked amazing, but was I going to colour the scarf?

When I knew the scarf was going to be white, I KNEW. I felt it in my gut. But I also knew so little of the rest of the piece then. I hadn’t yet spent hundreds of hours with this Bodhisattva. I hadn’t known how I would approach the colour of their body.

I texted him back that it was fitting I had not sealed the piece, even though I could have. It hadn’t felt right, and this was probably why. While it would require some colour testing, because the scarf was coloured with white pencil crayon, which is wax, it was possible.

I went back to my reference pieces. I looked at more images of this divine being, depicted across cultures and countries and transcending written languages. The scarf wrapped around their body and entwined with their many arms was almost always green.

But of course.

Green Tara. The Bodhisattva of compassion. And here is Avalokiteshvara, the embodiment of all of the compassion of all of the Buddhas that ever were and ever will be. Avalokiteshvara from whom it is said Green Tara was born, sprung from a single tear that fell from their eye.

I chose the colours and I got to work. The effect of wax on more wax is silky. The scarf came forth, smooth and shiny and rippling on its way around and through and billowing out.

On the final day, as I finished the last loops of fabric in green, I felt a settling in my body. It was a sense of ease and comfort, of “Ah yes. This is ready now to share with the world.”

And then it was done.

Coloured pencil for those of you not in Canadia.

Dearest Kait, We are coming upon the end of this year 2024. I want you to know that I've had your writing -- this post sharing the long and gorgeous journey of your manifestation of this magnificent 1000-Armed-Avalokiteshvara -- open in one of my browser tabs since you posted it in August. I have revisited it frequently, sometimes daily as needed. There has been a special, multidimensional give-and-receive quality to this practice of revisiting this post that has helped me step up to my day -- with strong back and soft front -- and outstretch my arms to this world. I love you and I thank you for your being, and your practices -- and your sharing of your practices in such deep mutuality -- in this universe. Deep bows to you, dear dharma friend.